Interview by Andreea Apostu.

I met Daša Drndić (Croatia) and Dragan Velikić (Serbia) on a hot summer day, at New Europe College, were they were about to have a joint event one day later, together with Filip Florian: A Different Kind of Summer Salad. (Yugoslavian Style), a funny and rather intriguing name. The emotions were tremendous, but I soon discovered there were no real reasons to be shy or afraid: Dasa and Dragan were very kind, friendly and involved in our interview. In an atmosphere of laughter, English, Serbian, Croatian and Romanian words, we discussed many important topics, ranging from Eastern European literature, to Western taste and representations about the Balkans, from our countries’ book markets to favorite writers and… music. We talked about past and present, fascination and stereotypes, the meaning of literature and the way it is shaped by modern day society.

They also talked to me about how they discovered Romanian literature and about the ways in which we could improve the cultural relations between the countries of our region. One day later, several fragments of their works translated into Romanian were read by Filip Florian at New Europe College. I truly hope to see their works published soon in Romania and also those of other neighboring writers, without the now so necessary approval of worldwide fame. The shortest way from Zagreb to Bucharest is via Paris or Berlin, Dragan told me. We should change that. We should become pioneers in discovering each other’s rich world of words and try to translate our physical nearness into a cultural one.

- Daša Drndić

A.A.:Dragan, I know Dasa already came to Romania, for just one day and a half, in Timisoara, at an international literary festival. What about you, is it your first visit to Romania?

D.V.: Yes, in spite the fact that we are neighbours, I never came here, and so it’s my first visit and, I hope, not the last one, of course.

A.A.:What brought you here? Tell us something about the event that will take place tomorrow, Thursday, at New Europe College: A Different Kind of Summer Salad. (Yugoslavian Style).

D.D.: I really don’t know how the event will look like (laughs).

D.V.: In fact, the beginnings of our story are the months spent together with Filip Florian. We had the same grant in Zug, Switzerland, and we tied this friendship there, between Dasa, Florian and I. It was Florian’s idea to bring us together here in Bucharest and of course, to present our work, because I don’t have, for example, my books translated into Romanian, neither does Dasa. And maybe this will be the beginning of our presentation here as writers.

A.A.: Besides this friendship, this beautiful friendship that developed in Zug, what are the things that unite you, in your works, for example?

D.D.:I read Filip’s book „Little Fingers”, he gave it to me in English. It’s an excellent translation and a wonderful book. I am trying to find a publisher in Croatia, I see Dragan found one in Serbia. And I see that Filip was in Macedonia three or four days ago, he launched I think „Little Fingers” there. Our residence in Zug was in a single object (building) and we had to stick together. Filip went mushroom picking, and then we would prepare these mushrooms and eat them together. Or we would make pancakes together and eat them. Smoking was forbidden, so we had a little landing, where we opened the window and Filip and I smoked (laughs), smoked vigorously.

A.A.: Because you mentioned that even though we are neighbours, it is your first time in Romania, I was wondering, how known is Romanian literature in Serbia and Croatia, or the literature of other neighbouring countries?

D.V.: I want to give not an answer, but first a comment on your previous question. I mean, we are in an age and with such an experience, that friendship is possible only, first of all, between authentic literary works. I mean, I just read a few pages of Filip’s work, but we had a lot of conversations and I think that each of us has something to say in an authentic way. And that was the reason we found each other very close. About your last question, you know, my first relation with Romanian literature was through French Romanians, I mean Mircea Eliade, and then the pessimistic Cioran, his main works. I also read Romanian literature in magazines, and Dasa made me discover an author, that I bought and started to read, Max Blecher. He was translated into Croatian. In May I was at Rijeka, and Dasa told me some things about him and I started reading his book in Croatian, because it is not very different from Serbian. I grew up in Croatia, so I have no problem reading in both languages. He is a really good author.

D.D.: I donțt know when the film „Scarred Hearts”is supposed to be out. Is it out?

A.A.: It’s out, it’s out.

D.D.: How is it?

A.A.: So and so. I really find that his books are untranslatable into cinema.

D.D.: I thought so, there is this other book of his, with a funny title, that you cannot remember.

A.A. I think in English the title is „Adventures in immediate reality”.

D.D. Yes, that’s it. Recently, some Romanian poets and writers have been translated into Croatian. In Serbian I think Cărtărescu is wildly translated. His „Nostalgia” came out two or three years ago. Herta Muller also, I read all of her books. The first two or three are excellent, then I had some problems with them (laughs), but they are OK.

D.V.: She’s writing in German, I think.

D.D.: Yes, she is a German minority. You had a German minority, Hungarian minority etc. I read Adam Bodor, he is also a Hungarian, and he’s excellent. I also read Attila Bartis, a friend of Filip, he’s also a photographer. We have in Croatia quite a good young poet, of Romanian origin, married to a Croatian poet. They are like a team and they started translating contemporary Romanian literature. There is also Lidia Dimkovska, I don’t know whether you’ve heard of her, she is from Macedonia, but lives in Ljubljana. She’s bilingual, trilingual even. She lived for some six or seven years in Bucharest, and she did her doctoral thesis here, so she translates into Slovenian and into Macedonian Romanian literature. So it’s coming, you know, it’s pushing its way.

D.V.: I forgot something. You know, we had forty years ago, in Vršac… It is a city in Voivodina with Romanian minority, with a publishing house. The man who founded this publishing house, Petru Cârdu, a Romanian poet, also founded the International Prize for Poetry. Stănesco was translated very much in Croatian and Serbian and Cârdu’s publishing house, KOV, published a lot of Romanian poets.

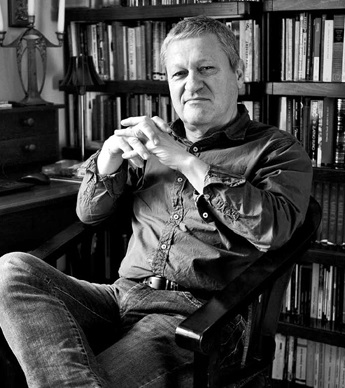

- Dragan VELIKIC

A.A.What do you think can be done more than this to improve, not only relations between Romanian and Serbian or Croatian literature, but the literary and cultural relations between the countries of this region, the Balkans? I find paradoxical that you know more about the West than about the neighbouring countries. You also told me that you found about Romanian literature by reading the works of French Romanians. What can be done to improve all of this, what would you suggest?

D.D. I’m a pessimist. I’m very pessimistic about literature in general. I think capital is becoming, I call it capitalist fascism. It’s losing its mind, it’s becoming hysterical, and it’s whipping out all values, that are not related to gaining money. And I think the future is quite bleak. Beginning with the educational system, the Bologna system that is programed to create cheap labor. You still have Cambridges, and Oxfords, and Yales and so on, that are not Bologna, for the elite who can pay. Look what is happening to the working class. All of this is reflected in literature. Those who read are less and less, they cannot grasp more complicated thoughts, they need it simple. The human brain is shrinking. I think we are doomed, in a way, unless there is a… revolution, to put it simple. I don’t think the times are good. But, as all systems and kingdoms have vanished, maybe this kingdom of capital will also fall apart one day, in 50 years, 100 years and something else will come. So, I don’t think much can be done. I don’t think we need governments at all anymore. Capital rules, banks rule, we don’t need parliaments, we don’t need parties, they’re just pawns.

D.V: On that topic, I think before the fall of the Berlin Wall, the relations between Eastern European countries were very, very close and literature reflected that. Today, a good Romanian or Bulgarian writer can be translated into Slovenian and Croatian or Macedonian only if he did something in the West. Then he is automatically translated. For example, in my case, the publishers in Eastern European countries decided to publish my book because I was published in German. The shortest way from Bucharest to Zagreb is via Paris or via Berlin.

D.D.: But then, what happened after the fall of the Berlin Wall: these Eastern European countries were sort of exquisite, they were interesting. And all literature that had to deal with life during socialism or communism was like sort of exotic to the West. I see what is happening now. These former Eastern European writers are becoming commercialized and their literature does not have the power it had at the beginning, and they’re not so interesting anymore to the West. But nothing is interesting to the West now. What the West publishes is mainly rubbish. What is not rubbish is read by a very small number of people. Of course there are good books, but they are not fast-food.

D.V.: Fast-food and vegan (laughs).

D.D.: No spices (laughs).

A.A.: Or books that want to seem profound, even philosophical, but that are in fact very superficial. That happens also a lot in Romania. In fact, in Romania, the book market is quite small.

D.V.: But you have 20 million people!

D.D.: Croatia has only 4,5 million people.

A.A.: Yes, but not all the people read, and the percentage of books sold compared to our population is much smaller than in the West. And I was wondering how does the book market look in Croatia and Serbia?

D.D.: In Croatia it’s falling apart, bookstores are being closed, big chains of bookstores are being closed. During the 2000s there was a boom, because the left party was in power and there were many small independent publishers who sort of flourished. Then the party and everything fell apart, these small publishers died, there is no more distribution, bookstores are being closed, less and less books are being published, and of course people don’t read. It’s quite discouraging actually. And then you have these young writers who want to become writers immediately, who don’t read. They go through one or two little workshops… When we started writing, we would first publish a fragment in a literary magazine, or in a literary newspaper, and then you would talk with your friends, you would send your book to your friends… Now they want immediately to be published. And what is published is of dubious quality. So you have a lot of writing that is not very good. And the critic reviews are smaller and smaller, monotonous, like schematic, they are not analytical, maybe in some literary magazines they are, but you cannot find those magazines in bookstores. So, literary criticism doesn’t exist anymore.

D.V: I don’t think people in Serbia read more than those in Croatia. But I think we have a very important book fair in the last week of October, and publishing houses have chains of bookstores and books are selling.

D.D.: Books are much cheaper in Serbia than in Croatia.

D.V: Yes, that is the point. You know, for example, my books in pocket editions are about 7 euros

D.D.: And mine are 20.

D.V.: And my book in Croatia is 20. That is 3 times bigger. And the life standard in Croatia isn’t three times bigger than in Serbia. I do not know what will be tomorrow, but for now there are a lot of bookshops in Serbia. For example, my publisher has 45 bookshops. OK, it’s the biggest publisher, but anyway, when you have that number, it means that you are selling. In Croatia I know that the situation with the bookshops was good ten years ago.

A.A.: In Romania we have the feeling, a sort of frustration, that we are a minor culture, due to history, context, economy and language, that we consider a sort of barrier. I was wondering if in Serbia or Croatia there is such a feeling.

D.V.: You can change that, you know. The only thing you can do is write the best that you can. Of course second class books written in big languages have more influence than first class books written in small languages.

D.D.: There is a discrimination…

D.V.: But what can you do?

D.D.: Nothing…

D.V.: Because today the problem is that American literature produces second class works, very boring, a sort of fast-food, and in small countries, with no critique, they take and publish everything. But you can change that.

A.A.: It’s a little harder to make it through, to be widely read and known.

D.D.: There is also this fascination of the Anglo-American world with European literature. I don’t know if you read this review of my book „Trieste” published in the „New York Times”, they said „high European culture”. This „high European culture” in my book was very simple, I have books with much more complex ”high European culture”, which will not go well in the United States. That’s a little bit too much. You pass the border. Max Blecher will not go well there. I was in Tuscany in some kind of residence, and there were these Americans that love Tuscany. They rent their apartments and they go there during the summer. I asked them: What do you read? The threw some American authors I’ve never heard about. And I asked: Have you read Kafka? And one of them said: „Which book would you suggest?” (laughs). We are centuries apart high American literature and high European literature. It’s moving more and more apart. We can talk about Faulkner, Singer, Nabokov, but Nabokov….

D.V.: That’s the problem, they have a lot of good writers from Europe. (laughs)

D.D.: Like filmmakers. The basis of the American film was put by Europeans that were running away from Nazism.

D.V.: I will give you an example too, about this trivialization and commercialization. One of the biggest publishers in Germany, Hanser, published my last book, „The Investigator”. They changed it a little bit, nothing very important. But at some point, my hero said to himself a poetic sentence and added: „Oh, Mayakovski in me!”, because it was a verse from Mayakovski. And she said: „Oh, it will probably puzzle the German reader, we should maybe put it out”. Because today nobody knows who is Mayakovski. And I said: „Yes, but they need to learn”. Can you imagine? Of course, I write for readers that are, let’s say, serious, I’m not reading or writing books just to kill time. Can you imagine then? I am completely sure that in Romania that would not have happened, my experience with Eastern European readers is that they are more open. I am sure that no Romanian or Bulgarian publisher would have cut Mayakovski from my novel. But in Berlin there is this Americanization. I am not a xenophobe, but please, I can’t do this, cut a part of my work for these reasons. (laughs)

A.A. Because we arrived at books, can you chose one of your books that you would recommend to Romanian readers and describe it a little, or tell us why would you recommend it?

D.D. I don’t like talking about my books, but the one that has been most translated, in 14 or 13 languages, is „Sonnenschein”, translated in some countries „Trieste”, or with other titles, maybe because it was the easiest to follow. The book is about the Second World War. There are these Internet pages where you have stories of victims of the Holocaust, the survivors, their families. And among these web pages I found some kind of confession by a man from a family in Italy. This novel is settled in Northern Italy and part of Slovenia, that was then called Adriatische Kusterland. This family survived because some of the members joined the fascist party of Mussolini, they had the fascist party’s membership cards. They were Jews, of course. They were transferred to Albania, when the fascists conquered the country. And it was very pathetic, it made me angry, this story did not fit, they were not victims of the Holocaust. OK, they found a way to survive, but it was not fair to have this pathetic little story among these horrible stories of survivors. And I said, aha, now I am going to write a book about this. And I made one of the members of this family have a relationship with an existing SS officer, which was an invention. I had a lot of complications with that book, because some of the members were alive and they came to the promotion, in Great Britain. So, anyway, I had her have a relationship with an SS officer, who died, and they had a son. It was at this point that I introduced the relatively unknown or recently uncovered story about the Lebensborn, the children who were stolen from Eastern Europe in order to be educated as Arians, because not enough Arians were being born, so 250.000 were stolen and educated as Germans. So… that would be one of the books.

D.V.: Hmm to recommend… probably the last three books. The last one is „The Investigator” and it is let’s say a family story, but also about the second half of the 20th century. „Bonavia”, the previous novel, is a story situated in this Eastern European area, about the catastrophe of Yugoslavia and the people who moved from Serbia to Hungary or Austria. And the „Russian Window”, who is also a transition story. Those three books communicated well between them and were the most translated, into 10 languages till now.

D.D.: I have also a book called „April in Berlin”, were I have the passage about Nora Iuga. (laughs). We spent some time in Das Literarische Colloquium Berlin together and she told me about her life. I am obsessed with names. In the last two or three books of mine I have lists of names because I think that is the only identity that is important and that is left to us. Which history, which country, which hometown, which language, I don’t think those are important identities. Our name and, perhaps, the language that we used to write in are the only things that count, really. And, you know, this idea of generalizing. What is history? History is the lives of these so called little people. They make history, not big history. Big history is heartless and it has no identity. These little stories are the stories that count. So, I’m obsessed with these names, I have lists and lists of names. In „Sonnenschein” I have 9000 names.

D.V. Ordinary life is something that interests me as a reader. When I read such a book, where I have the space and the time far away from my time, I enjoy it. Those are the books that I try to write. When I published my first book in German, my neighbour in edition was Gellu Naum. I read him a little bit in German during that time, my German wasn’t that good back then, but I have the book at home, I can read him now. And my publisher visited him. He lived in the suburbs then, he was such an unusual person!

A.A.: You said that literature should be related to real life. Does it have to be a sort of documentary, does it have to document real life?

D.V.: Of course. I think through the good books we can touch the past better than from the history books. The common history is the history with a big H. In literature we have history with a small h. It means that you learn more from literature about the ordinary life in the 18th century, for example, than from history books. For example, you can always acquaint to such territories, Musil’s Vienna is still there, even though Vienna is another city, and it is the same for every book. For example, the most famous book, „Alexanderplatz”, today Alexanderplatz is totally something else than before. But you have in common the past, the time, and the space. I enjoy reading such books, because I am richer then, I gain more experience. I think literature, art, can give you some firsthand experiences.

D.D.: In my books, at least in the last five or six, I deal with these two evils: the Holocaust and the communist regime. But never making them equal, because they are not equal. Within these two areas I find fascinating little stories of everyday life and of horrible suffering. And those are, like Dragan said, the stories that really make history. Official history is dry and heartless. The more you investigate, the deeper you dig, the more fantastic stories you find, and then you can empathize with them, identify with them in a way, because unfortunately this evil does not end. We see this rise of fascism again. You see what’s happening in Poland, in Hungary, what’s happening in Croatia also, in France. The danger is permanently here.

A.A. Is this historical background somehow specific to the Balkans?

D.V.: I used to say, but that doesn’t mean I was right (laughs), that between Odessa and Trieste there is more literature than between New York and Los Angeles. Because you have a lot of small worlds that produce authentic literature. What I don’t like are these campus writers, that come, hungry for experience, in Europe, and then in two month they collect some informations. There’s an American writer that wrote a book about Hungary, after staying only a couple of weeks, he went around… Of course, this is not very good literature. The best compliment I’ve ever received was for my novel „The Russian Window”. I stayed two years in Hungary, after the NATO war in Serbia. The Budapest NOAR, a magazine, wrote about my book, that had about one hundred pages about Budapest, that „finally some foreign writer that can discover us something about Budapest that we didn’t know”. It doesn’t mean it is a good book! (laughs) I think that we, here, in Eastern Europe, are rich in various experiences. It’s like a pot, there are many languages, and everything is in relation with one another. It is why I think we produce so much good literature. We have more writers on every square meter than in many other parts of the world. In each country you have 10 authors that are known and translated into other languages, and that’s something.

A.A. For example, in France, in recent years, you don’t have the same amount of good writers. So many things happened in this area and there is so much culture here, that this led to an explosion of literature.

D.V.: For example Hungarian literature. They have a lot of very good authors. In Croatia, in Bosnia, in Serbia you have very good writers. But Hungarian writers have so many worlds, and they are so exciting.

A.A. Did you find some similarities between authors from the Balkans? A sort of Balkan style?

D.D.: No, no…

D.V.: No, but in the West they want to see that style (laughs). No, can you imagine, Esterhazy and Florian or Dasa! Totally different worlds! They just want to see this „Balkan style”.

D.D.: But there is something. There is a slight similarity maybe, I don’t know enough, I haven’t read enough of all these Eastern European writers, but it might be like a fil rouge in the themes that they use when describing life under communism. It does not have to be directly, but these sparks are what the West wanted to hear. On the other hand, Yugoslavia was outside of the Eastern Block so the themes were different, really. We had this Black Wave current in film, you had subversive literature in the early 70s, you had subversive art, that passed, that existed, with difficulties, with restrictions, but it was not suppressed. So the themes were a bit different in literature, as in art. We had social-realism till the early 50s, then it went away. You see, maybe this little red thread in Eastern Europe literature is this dealing with the horrors of the system, from the way the people lived, the housing, Nora Iuga not writing or getting drunk in the Writers’ Society and writing her poems on napkins. There isn’t much of this in the literature from former Yugoslavia. There was a lot about the Second World War, the partisans, the anti-fascism fight, there were films about this. But the Black Wave was very modern, in film, in literature.

D.V.: There is a certain phenomenon. With the catastrophe of Yugoslavia, in the West they had an imagination of Yugoslavia and what was going on during the war. And there were authors that tried to guess what the Western audience expected and they were writing the books that were expected in the west. They were full of stereotypes. The authors weren’t fighting their times, they were producing.

D.D.: The same thing that happened with Eastern European writers after the fall of the Berlin Wall happened with Sarajevo. With the siege of Sarajevo that lasted four years, you had this amount of literature dealing with the war in Bosnia, which was interesting for the West. Now that has blown out, flattened.

A.A. It was just a kind of literary fashion.

D.V.: Yes… and I remember now that some American television came and wanted to speak to a raped woman who speaked English.

D.D.: A raped woman?

D.V.: Because the audience would be more touched if she spoke English. Can you imagine that? They came with that wish: „We need a raped woman who speaks English”.

A.A. They just wanted to sell and use people’s feelings. You mentioned Nora Iuga, at some point, Dasa, and I remembered the status of poetry and prose now in Romania. I find that there is a sort of gap: poetry seems to be blooming right now, with many new, young, impressive poets, but novels or short prose are not keeping up the pace. They appear more rarely and we cannot see the same number of new voices. What is the situation in Serbia and Croatia?

D.D.: In Croatia poetry is almost banned (laughs). Nobody wants to publish poetry, there are two or three publishers who do it at their loss. It is being written and there are young poets, good poets, but you cannot have a boom if nobody wants to publish them. There is also something else: even if they are published, nobody reads poetry.

A.A. In Romania there is quite the same thing: not a lot of people read poetry, but those who read are constant and the public is getting bigger and bigger. You can feel the new wave of interest, and these four or five publishers are doing their best to promote contemporary poetry.

D.D.: Well that’s wonderful.

D.V.:We have a lot of novels. The authors are not young now, but, for example, Marojević is now middle aged. We have novelists, but, you know, to be one, you need more time.

A.A.: And there is something else: as I was talking to Dasa before the interview, we don’t have residences for artists and writers here in Romania.

D.V.: But you are not in the Traduki family?

D.D: There is this organization, Traduki, it’s like an umbrella organization for all these residencies in Europe. They organize and they control, and they have competitions and an overview of the residencies in Croatia, in Albania, in Kosovo, in Bosnia, in Slovenia.

A.A. I know that we had some residencies under Pro Helvetia, but they withdrew from Romania, Filip told me about this in our interview. Unfortunately the government wasn’t able to create at least 4 residencies for Romanian writers.

D.V.: Oh, so they are for Romanian writers?

D.D.: In Serbia and Croatia they are for foreign writers, we don’t have for Serbian or Croatian writers.

A.A. In Romania we don’t have any, neither for us, neither for foreigners.

And now, as the end of our interview approaches, I will ask some easier and let’s say funnier questions. For example, which writers changed radically or had a big influence on your writing? At the beginning?

D.D.: I don’t know when the beginning was, it was a long time ago (laughs). But what comes to mind immediately is Thomas Bernhardt, because he gave me the courage, I saw that you can be angry, you don’t have to be polite, you can be nasty, you can criticize. And while reading him I was so happy that I had the right to be angry: with my country, with politics. Because during this old system I was just thinking now: you could talk softly against your country and the party at home. When you went abroad that was sort of forbidden. You weren’t supposed to criticize your country and also it was also preferable to drop by the embassy or the consulate and tell them you were there. And Bernhardt said, when I read his first book translated into Serbian, it was „Frost” I think, some thirty years ago, then they discovered him in Croatia, so, when I first read him I thought: „This is wonderful, you can be angry, you can curse, you can really say what you think if you really know how to say it. He’s one of my favorites. Not to mention some classics like Kafka or Musil. But some authors don’t function anymore. This is going to sound horrible, what I am going to say, but I took Marguerite Yourcenar again and I couldn’t read her. Maybe it was something wrong with me, I don’t know.

D.V.: I have the same problem with Borges.

D.D.: I didn’t touch him again. I don’t know if I can read Dostoyevsky again, for example, I haven’t tried.

A.A. I had the same experience with Dostoyevsky, even though I like the ideas, there is too much philosophy and too little literature there.

D.D: It is too heavy.

D.V.: Too artificial.

D.D.: From Marguerite Yourcenar I also read this short little novel, Le coup de grace. It goes on and on, it made me nervous, it’s 100 pages long, and it really made me nervous after 50 pages, it’s repetitive. Also Thomas Mann – I cannot, I really cannot! I took the Magic Mountain, and the beginning goes on and on, he’s on the train, I know what will happen, but, I don’t know, it was too much!

D.V.: I think that I have a couple of writers that really changed something in me. For example, I have Ernesto Sabato, I read his Tunnel, and then The Heroes and the Gods, a really marvelous novel. But for years my love was Nabokov, but now I don’t know if this author is translated in Romanian, it’s Gaito Gazdanov, it’s the same generation of Nabokov, but with the experience of the Revolution. And he moved after the revolution, in 1918, to Paris, and he was a taxi driver in Paris for 20 or 30 years. And Gaito Gazdanov today is a sort of new classic in Russia, translated into Serbian, for example. When I was a publisher, I published his novel The Night Roads and he is the same quality as Nabokov, but without Lolita. Because Nabokobv, without Lolita, would have been well known, but only between the people who really had the taste. One of the authors which, whenever I read his books, for the second or fourth time, were just as fascinating, is Isaac Bashevis Singer. I like him very much.

D.D.: Babel is fantastic for me, I could go back and back again to him.

D.V.: The Master and Margarita, Bulgakov! Please! I mean, I read it in grammar school, I read it as a student…

D.D.: I also read it again two or three years ago.

D.V.: It works in a fantastic way. Even though he never saw his book published.

A.A. Latin Americans?

D.D.: Oh, there is Marquez, I never thought very much of him.

D.V.: Me neither, he is like Kusturica, anyway.

D.D.: Kundera, also, he is almost up there, but never goes through.

D.V.: But not Hrabal!

D.D.: Oh, Hrabal is wonderful! He is fantastic!

D.V.: You can always read his books for the second or third time. I used to say, when you have no push to read the second time a book, then it was not meant to be read. I read a couple weeks ago, Kafka’s friend, the story was written in America, and it’s fascinating how the common people can enjoy his art.

D.D.: There is also Robert Walser, I don’t know if you heard of him, a Swiss writer, he died a long time ago, at the beginning of the Second World War, a nice author to come back to.

D.V.: And the poets: Kavafi, Derek Walcott, the Nobel prize, the Homer from Antibes, then you have Brodsky, Zagajewski. Great poets! I like to read poetry when I write, because poets can have great novels in just one or two verses.

A.A.: And the last question: which character, from worldwide literature, would you like to be?

D.V.: Odysseus! (laughs)

A.A.: And you, Dasa?

D.D.: I never thought of that. I don’t have this need to be somebody else, at all (laughs). I’m not very satisfied with who I am, I am exceptionally satisfied with that but who I am is who I am. I never thought about this, this wish of being somebody else.

D.V.: Me neither, but you know, it’s just an example: „If…”

D.D.: I don’t even have the If! (laughs) I could wish myself to be a little bit different, better.

D.V.: If, that would be a good title.

A.A. I think it’s the title of a song from Pink Floyd actually.

D.V.: Oh, you are so young, but you know about Pink Floyd! In their case, when you listen to their albums, you find a totally different time, world, generation…

D.D.: Cinderella! I would like to be Cinderella! (laughs, Dragan laughs too)

A.A. With Pink Floyd and the 70s there is an interesting story. Our parents were fascinated with them, they were the forbidden fruit of the West.

D.V.: Oh, in Yugoslavia they weren’t forbidden.

A.A.: Oh, here they were quite rare, but you could still find them on the black market.

D.V.: But my favorite band from the 70s, you know, I was a musician at that time, is Jethro Tull.

A.A.: Yes! I love them, I know their music very well!

D.V.: Oh, I’m so happy! My wife hates them, she thinks I’m provoking her because of Jethro Tull. They are really something special. Aqualung, Heavy Horses, Minstrel in the gallery!

A.A.: Well, I would like to end our interview now, on this positive and musical note. Thank you very much, Dasa and Dragan, I hoped you liked this interview as much as I did. It was truly a pleasure for me to be here with you.